Nobody would think yak hair would be suitable for luxury jumpers. Where did you get the idea? “I used to live and work in Beijing and travel a lot to the border regions. I observed that the coarse fibre from the yaks was being used for ropes and tents but the soft fibre wasn’t being used at all; it falls off the animal and blows away in the wind.

“The rationale was that wool that keeps animals warm at 4,500 metres during the winter, in pretty tough conditions, clearly works well. The idea was to see how soft we could make it.”

How did you turn a whim into commercial reality? “I started the company with a friend, Aaron Pattillo, after we met on a mountain-biking expedition. At the time he was with the Clinton Health Access Initiative, working very much in the non-profit space, whereas I was in financial communications, which was very much in the for-profit space.

“We were looking to work together with something that was a for-profit business with social impact. We were convinced yak wool could have its own identity; people want to feel close to where their fibre comes from.”

The jumpers sell for up to £270 (US$345), a similar price to cashmere. Who buys them? “The demographic is 30- to 55-year-old professionals who appreciate quality and are prepared to pay for it. It is a premium product, not in the uber-expensive luxury space. Yak wool is softer than merino and has a more luxurious feel.

“When you ask someone what they think the jumper is made of, they touch it and say cashmere. Nobody guesses yak – some don’t even know what a yak is!”

Where are the products made? “The spinning is done in Italy and China and we use two knitwear factories – one in Beijing, one in London – owned by the same individual. For the yak wool sourcing we work with a company called C Yak that is a collection of cooperatives. I have been working with the founders for eight years.”

Do the herders ever see the finished products? “I was wearing a Khunu garment on a trip to the plateau; I wanted to show the Tibetans what we had made with the wool. They looked at this soft sweater, looked at the yak, looked at the sweater again, and started laughing in disbelief.”

Why Khunu? “It is the name of the first Mongolian dynasty, a confederation of nomadic people who ruled for more than 1,000 years prior to the rise of Genghis Khan. We felt this fitted with the brand’s objective of economic inclusion and connectivity.”

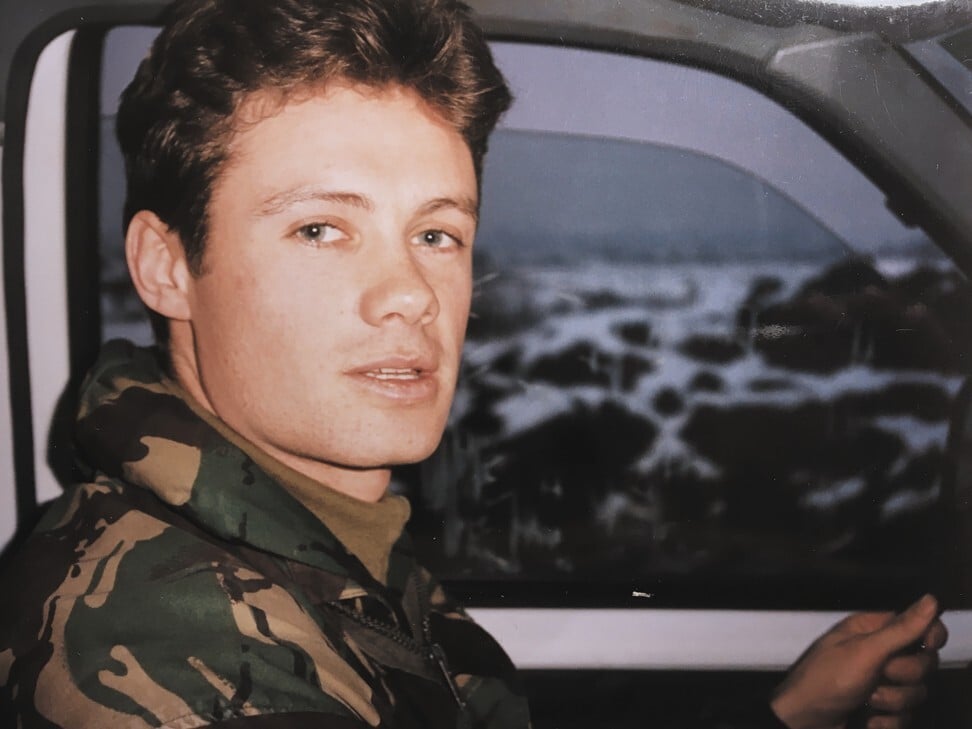

You were a captain in the British army, serving in war zones, including Bosnia, with the United Nations peacekeeping force. Did that experience help in the commercial field? “Well, it does teach you not to panic; to step back and look at the bigger picture and delegate well. With Bosnia, the only real way to get the place back on its feet was to have people with good ideas and build some real entrepreneurial infrastructure.”

What does the future hold? “We are getting outside involvement, management and investment from the Good Growth Company. They love the Khunu concept and have the infrastructure to take it to the next level.”